Source: CNN.COM – Br MJ Lee – October 17, 2016

Muslim Americans describe the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks as a seminal moment that painfully altered their place in American society.

But when CNN interviewed American Muslims about the presidential election, we heard a startling message: 2016 is worse.

CNN traveled last month to three growing Muslim communities — in Minneapolis, Northern Virginia and Staten Island — which represent the diversity and increasing political engagement of Muslims in the United States. The majority of people we spoke to said it is harder to be a Muslim American today than it was even after 9/11.

“I have never thought I would hear my young daughter say, ‘Dad, people were asking me about my scarf in the school,’ ” said Hamse Warfa, a Somali refugee who immigrated to the US as a teenager and now lives in the Minneapolis suburbs. “After 9/11, there was no ring-leader, so to speak, who was championing, mainstreaming, hate.”

That “ring-leader” Warfa was referring to is Donald Trump, the Republican nominee for president.

Trump has run a hardline, anti-immigration campaign built on promises to erect a wall and deport millions of undocumented immigrants. Last December, he announced a proposal to ban Muslims from entering the country. And he has suggested that profiling would be an effective strategy to prevent terrorism.

CNN interviewed more than 40 Muslim Americans who expressed raw emotions ranging from disbelief to anger to fear. Perhaps most disturbing about this election, many said, is the perception that Trump has helped to normalize animosity toward and suspicion of Muslims in the US.

These tensions have been exacerbated over the past year by a series of attacks carried out by individuals who claim to be motivated by radical Islam, and in some cases swear allegiance to ISIS.

Trump has repeatedly seized on these moments to question the loyalty of all Muslims. He did so as recently as the second presidential debate, when a Muslim woman asked Trump and Democratic nominee Hillary Clinton: “With Islamophobia on the rise, how will you help people like me deal with the consequences of being labeled as a threat to the country after the election is over?”

Trump responded by calling for “extreme vetting” — and for Muslims to police one another.

“We have to be sure that Muslims come in and report when they see something going on. When they see hatred going on, they have to report it,” he said.

Clinton told the woman: “I’ve heard this question from a lot of Muslim Americans across our country because unfortunately, there’s been a lot of very divisive, dark things said about Muslims.”

The two candidates meet again Wednesday in Las Vegas for their final debate.

Hate crimes against Muslims appear to be on the rise — researchers at California State University found that they were up 78% in 2015.

Hina Ansari, an American-born Muslim woman who lives in Woodbridge, Virginia, told CNN that she found Trump’s rhetoric about immigrants “terrifying.”

“I’m imagining internment camps for all of us if Trump won the election,” said Ansari, who supported Bernie Sanders during the primaries and now backs Clinton. “The way that he talks, the hate speech that he uses, that he brings people towards him — it’s scary to know that so many people who seem like perfectly reasonable people that I know support him.”

Concern has become a catalyst for action. Immigration advocates across the country have launched local and statewide voter registration campaigns, including efforts aimed at bringing into the fold first-time Muslim voters.

Those votes will become increasingly important. Muslims make up a small slice the country — the Pew Research Center estimates that there were about 3.3 million Muslims in the US last year — but by 2050, Muslims are expected to make up 2% of the country’s total population.

Amin Shehadeh, a 47-year-old Palestinian American who has been a US citizen since 1996, will vote for the first time in his life this November for Clinton.

“Because I don’t like Trump,” Shehadeh said. “This year, my daughter, she make the registration.”

Hundreds of worshippers have filed into the Dar Alnoor mosque in Manassas, Virginia, for Friday midday prayers. Imam Sulaiman Jalloh speaks with urgency, pleading with his congregation to take action: Come November, he says, everyone must get out and vote.

“Today, some people say, ‘You and I have no right to be here.’ That although this nation was founded on freedom of religion, your religion and mine is not welcome here,’” Jalloh says. “My dear respected brothers and sisters: This time, I believe none of us has the option to just sit home.”

There is little doubt that the Imam is referring to Trump’s rhetoric during this campaign.

Many Muslims in Northern Virginia whom CNN interviewed said they are obsessively following the election. In places of worship, community centers and schools — both in private conversations and in public — Muslims of all backgrounds worry about the toll the campaign is taking.

Even children are not immune.

At the ADAMS Center’s Radiant Hearts Academy in Sterling, Virginia, where preschoolers to second graders are taught a curriculum centered on Islamic values, teachers and parents are grappling with how to explain the election to children.

“You can’t really hide it, you know? If it’s in the news and your parents are watching the news, it’ll come up and the word ‘Muslim’ will come up,” says Hurunnessa Fariad, the school’s vice principal.

Originally from Uzbekistan, Fariad moved to the US when she was little and now has four daughters.

“You have to constantly tell your children, ‘No, we’re not going anywhere. We’re here, you know, we haven’t done anything wrong,’” she tells CNN. (Fariad doesn’t want to share who she will vote for in November, only saying: “It’s obvious.”)

Sadia Naureen is a 16-year-old resident of Falls Church whose family is from Pakistan. Naureen says she has heard multiple stories about Muslims getting attacked and women choosing to take off their hijabs. She no longer feels safe walking alone.

Naureen blames Trump for making her fear for her safety.

“He should know that the stuff he’s saying is really affecting people. It’s not just words anymore to get votes — it’s going to change people’s lives for the worse,” Naureen tells CNN.

Dar Al-Hijrah, where Naureen’s family worships, felt shaken in November when a man left a fake explosive device at the mosque. Months later, a sign in the lobby cautions that in light of the shooting of an Imam in New York City, Dar Al-Hijrah’s security is monitoring all suspicious activity.

Although she is not old enough to vote, Naureen is an avid Clinton supporter and is working with an immigrant rights group to encourage people to register to vote.

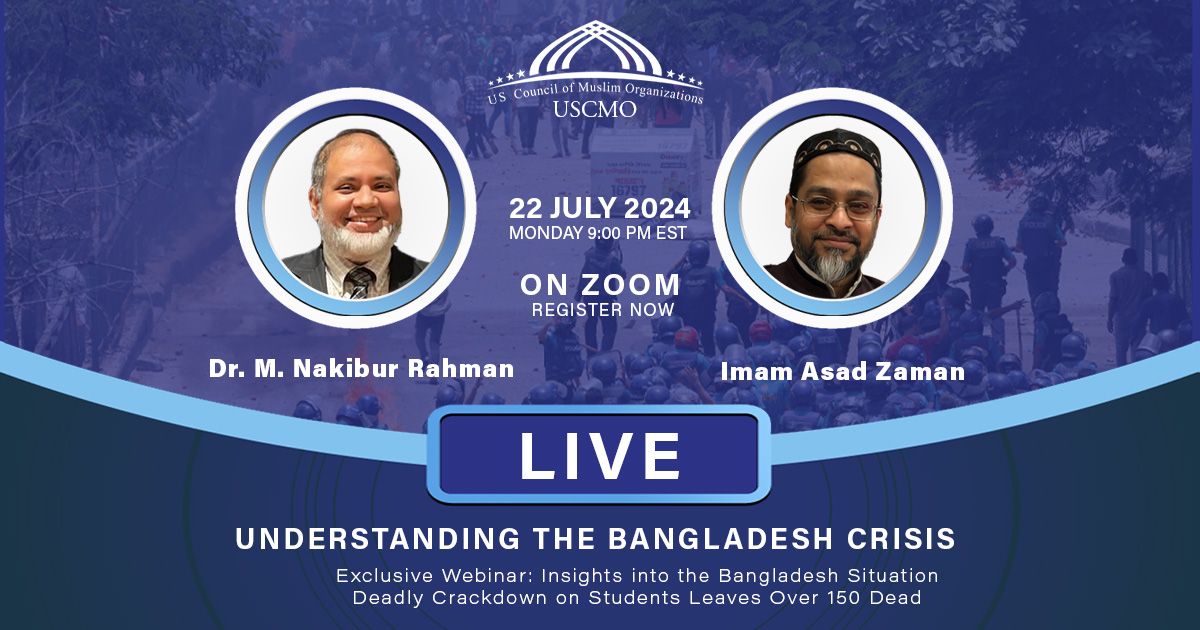

The US Council of Muslim Organizations, one of many groups involved in voter registration efforts this year, said as of last month, it had helped an estimated 500,000 Muslim Americans register to vote this cycle.

The influx of new Muslim voters — many of whom are turned off by Trump’s message this year — along with anecdotal evidence of Republican-voting or independent Muslims turning their backs on the party this year, could haunt the Republican Party far beyond 2016.

David Ramadan, a former member of the Virginia House of Delegates and an Arab-American who comes from a Muslim family, suspended his membership with the Republican Party when Trump became the presumptive nominee.

“I was absolutely distraught and offended that my party, the party of Reagan, the party of Lincoln, the true big tent that aspired for a great America, has today nominated a candidate who is a bigot, racist, demagogue,” Ramadan says in an interview at his home in Dulles, Virginia.

Born and raised in Lebanon and a life-long supporter of the GOP, Ramadan doesn’t yet know what he will do after the election. He predicts that the political views that take hold among ethnic minorities this year will far outlast the 2016 election.

“They’re saying, ‘What happened here? We need to be more involved so that we don’t see this rhetoric again,’” Ramadan says.

Da’in Johnson, one of the worshippers at Dar Alnoor who works for the Department of Labor, says the silver lining for Muslims in the 2016 election is that the community is being forced to “step up our game.” Part of that effort, Johnson says, is making clear to political candidates that no Muslim vote should be taken for granted.

“I think that no reasonable-thinking Muslim likes or agrees with what Donald Trump is saying,” Johnson, 55, says. “But it’s not a lock step for the Democratic nominee.”

For rest of the story, click here.